Part 2: Reimagining the Streets of Southwest Connecticut

Vision Zero, Complete Streets, a Safe and Livable Streets Ordinance—these are just some ways communities in southwest Connecticut are reimagining their streets.

What would our streets and roads look like if they were designed to truly accommodate all of its users, including drivers, pedestrians, cyclists, and public transportation? Communities across southwest Connecticut are looking to answer this very question.

Let’s take a look at how some municipalities are reimagining their streets to make them safer and more accessible for all users.

Norwalk: Enacting Complete Streets Policies and Guidelines

Picture a street with two travel lanes, allowing cars to move in either direction, separated bike lanes, and wide enough sidewalks to have room for pedestrians to walk next to other amenities like street trees and benches.

That’s the vision behind Complete Streets, a transportation policy and design approach that aims to take all users into account in roadway and project design.

“In the simplest terms, it’s really streets for everyone and streets about the people,” said Garrett Bolella, Norwalk’s assistant director of Transportation, Mobility, and Parking at the February 2024 meeting of the Common Council’s Economic and Community Development Committee.

Norwalk is currently in the midst of developing a set of Complete Streets design guidelines and implementing a Complete Streets ordinance, which would require the guidelines to be put into action.

“They’re really a means to an end for us to achieve several of the ambitious goals we have—whether that’s safety and reducing fatalities and serious injuries on our roads, whether it’s achieving our environmental and sustainability goals that we set out, whether it’s supporting economic development,” Bolella said. “And I think all of this in the end is going to result in a more livable city.”

The guidelines would have information such as how wide the roadway should be, what the speed limit should be, and how much room for sidewalks should there be that the city and developers would follow as they work on projects going forward.

Michael Morehouse from FHI Studio, the city’s consultant on the project, said that having an ordinance on the books, in addition to the design manual, would create an enforcement mechanism and provide “clear accountability.”

Bolella and FHI Studio will be presenting this to the Common Council’s Ordinance Committee on Tuesday, May 21, the first step in creating the ordinance.

“We see moving through the ordinance committee over the spring,” Bolella told the Economic and Community Development Committee in May. “We hope there will be a draft ordinance early in the fall, adoption by the end of the year.”

In June, the department is also planning an “active engagement” project in June at North Main Street and Ann Street, where community members can help create a temporary Complete Streets project.

Some community members have already voiced their support for the city’s efforts to make Norwalk streets more walkable and safer.

Tanner Thompson, chair of Norwalk’s Bike/Walk Commission, highlighted to the Economic and Community Development Committee in May, the importance of a transportation system that isn’t solely reliant on one way to get around.

The crash on I-95, which closed down the roadway and rerouted cars through the city, grinding traffic to a halt for a few days, “underscored importance of building a transportation system that is resilient,” as well as “the need for a transportation system that is not wholly reliant on driving.”

“I think that through Complete Streets, we can have a more diverse transportation network, that people have options so that we don't grind to a halt when there's a crisis,” he said.

Stamford: Vision Zero, a Path to Zero Traffic-Related Deaths

In Stamford, the city is working on a Vision Zero action plan that aims to help eliminate traffic-related deaths by 2032. Vision Zero is a strategy which works to eliminate all traffic fatalities and serious injuries and improve mobility for all.

“Vision Zero, is our citywide roadway safety effort to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2032,” said Luke Buttenwieser, a transportation planner in Stamford’s Transportation, Traffic, and Parking Department. “It's not just our department that's working on this, but we're partnering with the fire department, the police department, the operations department, 911 emergency communications—it's really a whole city wide effort. It's integrating roadway safety into every single aspect of the city.”

The concept works to shift the burden away from being only about an individual’s behavior and focus on creating systems that help achieve the zero-death goal. That could look like narrowing a roadway to make cars pass slower or separate bike lanes so cyclists aren’t mixed in with drivers.

“We also operate in a system and networks of transportation, where, as a system it’s needed to be entirely safe, so if there are mistakes, because we're human who can make mistakes while driving right, or moving around in other ways, we don't want that to end up being a fatal mistake,” said Mike Lyden, a consultant with the organization Street Plans, which is putting together Stamford’s Vision Zero Action plan.

Buttenwieser and Lyden spoke at a Vision Zero kickoff event on May 7, where more than 30 attendees heard a presentation and had a chance to provide feedback on what streets and intersections efforts should be focused, what types of road designs they liked, and what the most important priorities of the plan should be.

Lyden told the Transportation Committee in April that they’re “really leaning on a lot of data that’s been collected” as well as “analysis that we’ve been doing to really look at where the most problematic intersections and street segments are across the city.”

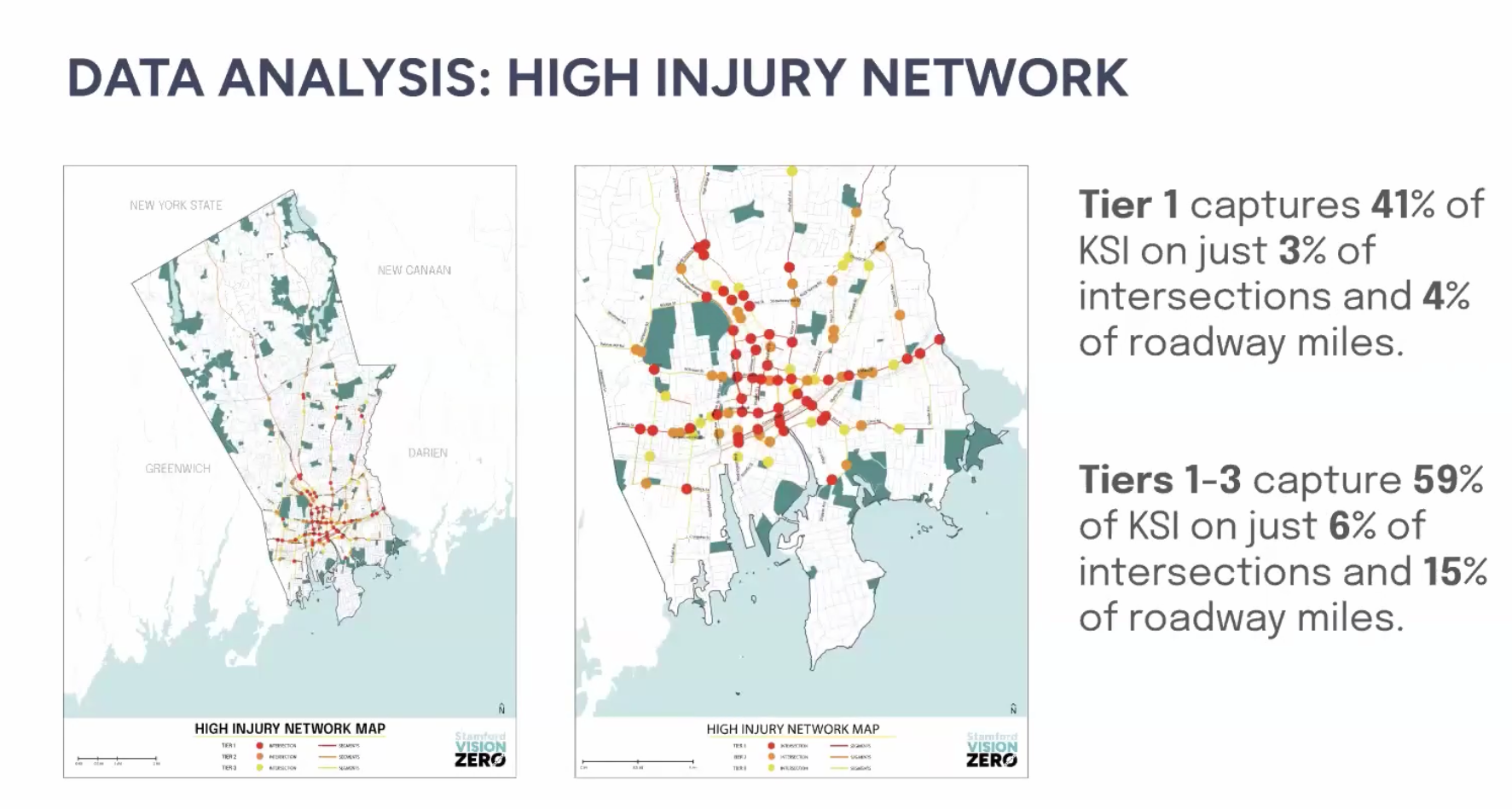

So far, based on the data, they’ve grouped the roadways into tiers, depending on how many crashes occur on that road or at that intersection. Tier 1 includes just 3% of intersections across the city and just 4% of roadway miles, but has 41% of crashes that result in someone being killed or being seriously injured. Tiers 1-3 have just 6% of intersections around the city and 15% of roadway miles, while including 59% of all crashes in the city that result in death or serious injury.

Lyden said that this type of data helps them focus their efforts, noting that interventions on just the Tier 1-3 roads could have a dramatic effect since they make up almost 60% of the city’s worst crashes, often called KSI (killed or serious injury).

“What really surprised us is the number of crashes and KSI crashes that are happening particularly around city parks,” he noted.

Lyden said Stamford is interesting because it goes from an urban downtown to surrounding suburbs to an almost rural environment in North Stamford. They plan to come up with different strategies to address different areas, to make the plan “really neighborhood-based.”

“Downtown is not like North Stamford—there’s really different types of solutions and responses on how we can help make the city safer for everyone,” he said.

The city was already working on implementing nearly 20 pedestrian safety pilot projects across the city, including adding bump outs to make it easier for pedestrians to cross a road or left turn calming measures, as a part of its Vision Zero efforts.

Fairfield: Implementing the Safe and Livable Streets Ordinance

Last year, when current First Selectman Bill Gerber was a member of the town’s legislative body, the Representative Town Meeting (RTM), he spearheaded an effort to pass a “Safe and Livable Streets Ordinance.”

“The Safe and Liveable Streets Ordinance stems from years of living in Fairfield—nearly 10 years as a member of the RTM—participating in the town’s processes to try to get traffic calming measures in place, talking to residents, working with bikers and walkers and hearing their frustration with the process,” Gerber told the RTM at its September 2023 meeting.

It also came at a time when the town was dealing with two fatalities of pedestrians hit by vehicles in areas without sidewalks.

“In too many areas of Fairfield, our streets are not safe enough to walk, bike, or even drive on,” Gerber said.”They’re not up to the standards of a forward-thinking municipality.”

In 2018, the town put together a Complete Streets Policy, which was endorsed by the Board of Selectmen at the time. The policy aims to outline “how the Town of Fairfield considers the needs of all of users when planning and developing transportation projects on town roads.”

However, Gerber said that this policy and the Bike/Pedestrian Master Plan which was developed around the same time, “have not been followed.”

“By September [2022] it became obvious to me that the plans and policies in place were not enough that we needed an ordinance,” he said. “An ordinance is a law … Policies are fine if they are mandatory—ours is not.”

The Safe and Livable Streets Ordinance requires a full-time Complete Streets Coordinator, who is “responsible for understanding, focusing on, and facilitating the implementation of Complete Streets in Fairfield.” It also requires the town to develop a right-of-way manual including design and materials standards, as well as a Complete Streets Plan which would include a list of planned projects, their priority level, the projected timing of work, a proposed budget, expected funding sources, risks, benefits, and projected ongoing costs for operations, monitoring, and maintenance.

While the ordinance ultimately passed the RTM with a 24-10-4 vote, some members raised questions about the costs this ordinance would have on the town and if it would add another layer of red tape.

"I think we'd be doing our town a disservice to put something through that's just not done yet," said Jeff Steele, a District 2 representative during the October 2023 meeting when the ordinance was voted on. “We have questions, we don't know cost, we don't know a lot of things still.”

Steele said that he and others opposed were “not against safe streets. We want safe streets,” but they believed more time and input should have been put into the ordinance.

Gerber and others said that this would help the town take action, something Gerber is now looking to do as the First Selectman.

“We need something more concrete than inspire,” he said.

Stay tuned for part 3, where we’ll dive into the plans to redo and reconstruct some dangerous intersections and roadways across southwest Connecticut.