“Wealth of Scientific Knowledge”: The Importance of Water Quality Monitoring in the Long Island Sound

Across the Long Island Sound, local groups and organization are working to monitor the water quality to make sure it's safe for people and that its ecosystems are healthy.

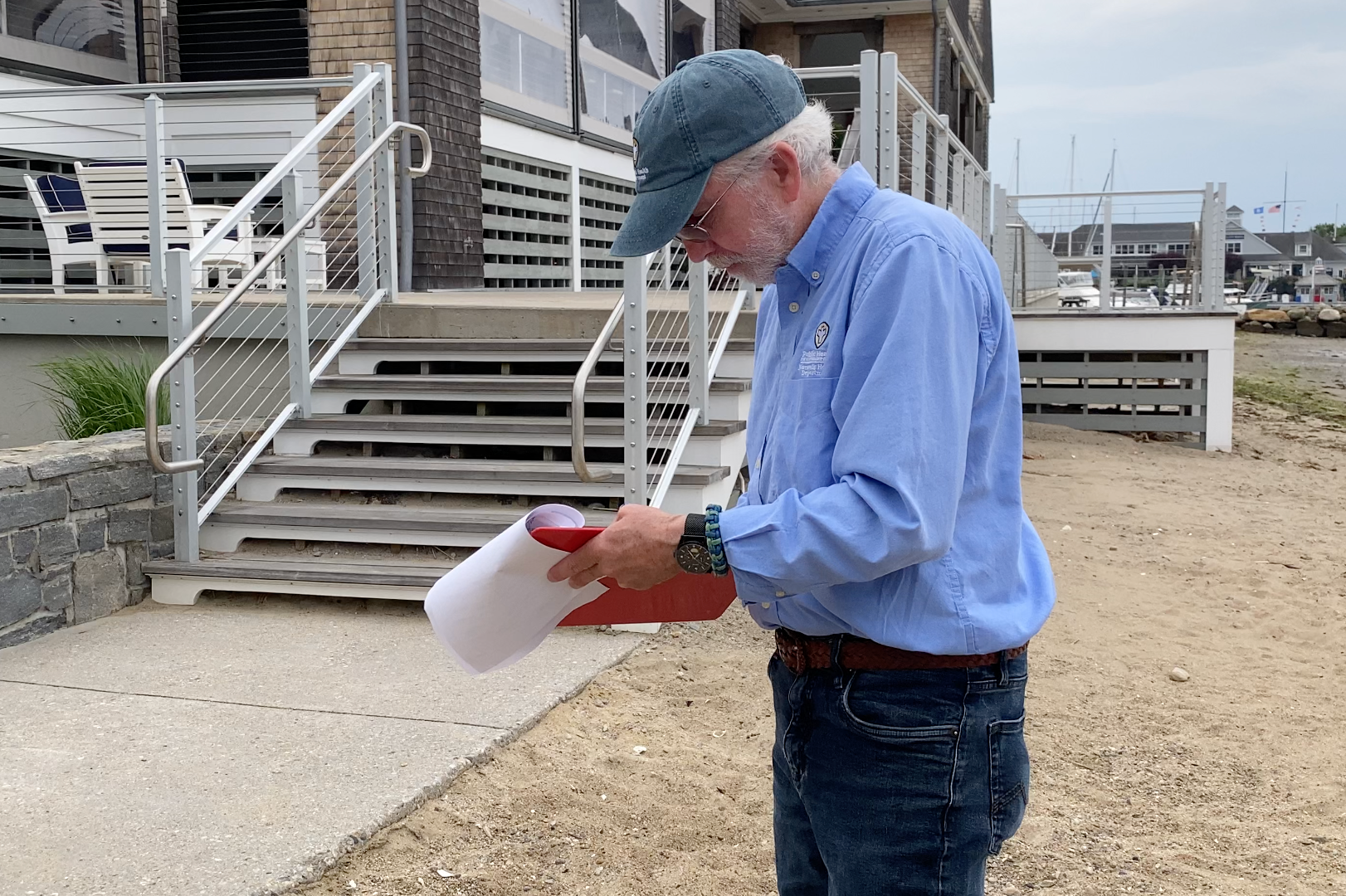

Every Monday morning, Norwalk Assistant Director of Health Bill Mooney and his summer interns get up before the sun and gather water samples at 15 locations across Norwalk.

In late June, Lili Tucker, an intern from Westport who is attending Auburn University as an environmental science major, was responsible for collecting the samples. Starting at Calf Pasture Beach, Tucker waded out until she was about waist deep in the water, plunged the container in her hand down into the water, and gathered a few ounces in it.

Each water sample was marked, tracked, and recorded by Mooney, before it was put on ice in a cooler. The samples would then be sent to the state lab for testing.

“We’re looking for enterotoxins,” Mooney said. “It’s an indicator organism, which indicates that there’s fecal matter either from an animal or a human in the water.”

Sarah Crosby, director of conservation and policy for the Maritime Aquarium, said that there’s two main areas of testing being done in the Sound—testing the water quality for people and testing the water quality for species and habitats.

“Water quality for people, we're thinking more about things like pathogens,” she said. “So when people are interacting with the water, is it safe for people to be in that water? Versus when we're thinking about water quality for species and habitats, we're thinking about temperature, we're thinking about salinity, we're thinking about dissolved oxygen.”

Water Quality Testing for People

Mooney and his interns are doing the first—testing to make sure the water is safe for humans. If the sample comes back with a higher level of enterotoxins than 104, they have to retest that area. If the sample comes back twice in a row above that level, they’ll close the beach and retest until the levels in the water have dropped.

“Anything over 104—we did have a failure a couple weeks ago, so we had to close the beach,” he said. “And then on Wednesday, we got through this whole process again, just with the failure. If somebody fails we’ll go back and retest it on Wednesday.”

If it still fails at that point, that’s when the beach is shut down until it tests below the level again. (Beaches are also proactively closed if there has been rainfall over 1.6 inches in a 24 hour period, since that means there’s a higher probability of runoff and stormwater impacting the Sound, as well as if there’s been a known leak in a nearby sewer system.)

The beach water testing Norwalk does serves as a public service to the community, Norwalk Health Educator Theresa Argondezzi said.

“The coastline and the beach areas in the city are such an amazing asset,” she said. “We love that the community loves them. We want to do the best we can to make sure the water is high quality and that we catch anything that we can early.”

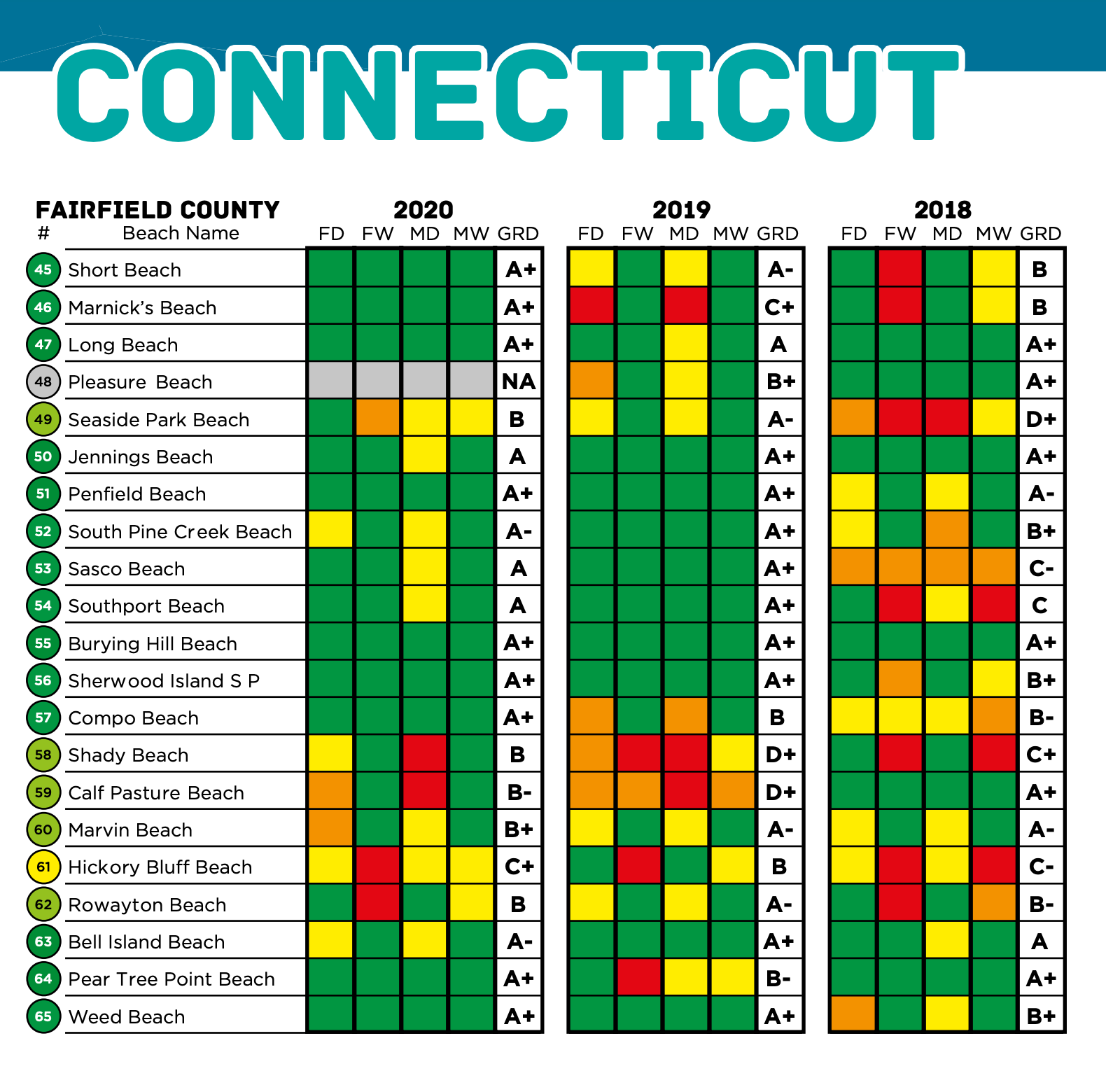

Save the Sound, a local nonprofit, publishes a biennial report that tracks how often the beaches along Long Island Sound were "found to be unsafe for swimming (frequency) and how high the level of contamination was (magnitude on the worst sampling day of the season."

The nonprofit that through its analysis it found "how hyper local water pollution impacts are."

"These illustrate how even within the same community, you can have a pristine beach and one that suffers ongoing pollution, highlighting the role of the local community in protecting or restoring water quality," the 2021 report read.

Testing for Ecosystems

Brittney Izbicki, a hydrologic technician, and members of the New England Water Science Center are currently monitoring the water quality in four embayments—or alcoves along the coastline that form a bay: Mystic, Norwalk, Saugatuck in Westport, and Sasco-Saugatuck complex, which is between Westport and Fairfield. The Mystic and Norwalk projects began in May 2021, while the other two sites began this year.

The testing is part of a partnership between Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the New England Water Science Center, a part of the United States Geological Survey, a scientific agency that aims to study the landscape of the country, its natural resources, and the natural hazards that threaten it. The plan is to build a statewide model that will allow state and local officials, as well as members of the public, to see how the data changes over time and by circumstance.

At each site, members of the USGS team go out and collect water samples near the surface of the water and near the bottom. At the start of their monitoring the team does “intensive sampling,” she said, where they go out twice a month to collect samples at the site. After the first few months, they move to sampling once a month.

The samples are collected at a variety of tidal cycles throughout the year to make sure that data is collected at different points. The samples are then analyzed for “nutrients, carbon, total suspended solids, silica, alkalinity, biological oxygen demand, and chlorophyll.”

Each of these samples help tell the scientists about the health of the water. For example, measuring dissolved oxygen can tell if there's enough oxygen in the water to support the fish and other organisms that need it.

Chlorophyll can be an indicator if there is too much algae in the water—too much algae can decrease the levels of oxygen in the water, produce a scum on top, and sometimes give off toxins.

“We’re water quality and hydrology,” Izbicki said. “We're mainly looking at the nutrient data to evaluate the (nutrient) loading that is occurring. We can look at different concentrations throughout the year, and be able to provide that information to the public and to the state.”

In order to collect the samples, Izbicki and her team boat out to sites, one usually near the top of the embayment and one near the bottom, and use a cylinder-shaped collector to gather water from near the surface and then near the bottom. The water is then poured into multiple containers that are sent to the lab to be analyzed.

In addition to the water sampling sites, USGS also has a few sites with continuous water-quality sites to capture data throughout the day.

“What we do is we measure six-minute data,” she said. “And we measure physical properties—temperature, salinity, light attenuation—and we're hoping to monitor the diurnal cycles [or cycles that occur every 24 hours].”

This allows them to see how the data changes throughout the weeks and months and under different circumstances such as high tide or low tide, Izbicki said.

The USGS continuous collection sites allow you to see how the different levels change.

The hope is that local leaders, state officials, and others can use the data to make decisions that relate to the Sound and its waterways, she said.

“This data is like a wealth of scientific knowledge available to the public and can be used for resource management and recreational [activities],” she said. “It's there as a tool for the state of Connecticut and local harbor commissions to be able to use that data to make important decisions.”

Partnering to Study the Sound

Many other organizations, such as Harbor Watch, a research program based in Westport that focuses on “Long Island Sound water quality, coastal ecology and the application of data to watershed management,” and Save the Sound, conduct water quality monitoring in the region. In 2017, Save the Sound launched the Unified Water Study: Long Island Sound Embayment Research, which the nonprofit organization calls a “groundbreaking water quality monitoring protocol developed so groups around Long Island Sound can collect comparable data on the environmental health of our bays and harbors.”

In 2022, the Maritime Aquarium hired Crosby, who helped launch the Unified Water Study while she was with Harbor Watch, as its director of conservation and policy, a new position that the aquarium hopes will “significantly expand the Aquarium’s leadership role in local and national conservation issues.”

“We’re involved in a lot of different aspects of water quality, and most of them are collaborative efforts,” Crosby said about the Maritime Aquarium’s water quality work.

The Aquarium participates in the Unified Water Study by testing sites in Norwalk Harbor.

“What that work does is really ties together what's happening along the coast with the existing monitoring, it's already happening in the central Sound,” she said. “The work that we're doing for the Unified Water Study is focused more on ecosystem health, so the fish and the dissolved oxygen.”

The Aquarium is also working on a new initiative this year, launching this fall, which will be a pathogen monitoring network, in partnership with Harbor Watch and the Interstate Environmental Commission.

“What we’re going to be doing is basically looking at where monitoring is already occurring across Connecticut and New York for pathogens—that would be things like E. coli,” she said. “So where is monitoring already occurring? And where do we have data gaps? Because a lot of our coastal waterways are not routinely monitored for anything.”

Once the group identifies where those gaps are, Crosby said that they’ll begin working to fill in the data gaps.

“We're going to play a coordinating role to make sure that we're really getting the information and that data to local and state managers,” she said.

How to Get Involved with the Sound

The work the Maritime Aquarium and Harbor Watch have been doing for the last few decades has allowed them to see the impacts of climate change up close.

“Certainly the water is getting warmer, we can see that not only you know, when you look at sort of global climate datasets, obviously, that is not news. But to see that play out locally, it really, I think, helps to sort of bring that home to people,” she said.

Crosby also noted that the data has allowed them to see the positive impacts efforts to improve water quality in the Sound have made.

“The patterns in dissolved oxygen are changing—I wouldn't say it's an entirely bad news story, because we have done a lot of really good work to improve what's happening in the watershed,” she said. “So our sewage treatment plants have gotten better, our land use has gotten more thoughtful.”

Still, Crosby noted the effects of climate change could affect that progress.

“It speaks to the need to work even harder to change the things that we can locally to help mitigate the effects of climate change,” she said. “And there's a lot that we can do with land use and conservation activities to prevent some of that damage.”

She encourages people to get involved with efforts at the aquarium or other local groups to help continue to make that progress.

“We have volunteer opportunities here at the Aquarium as well, but for someone who isn't local to Norwalk, but who wants to get involved, we have a terrapin tracking community science initiative, we have a frog watch community science initiative. So we have, I think, seven ongoing programs that people can get involved in to help us study habitats in their own backyard.”

She also encouraged people to participate in “one-off” programs, like beach cleanups that can really impact their community.