Southwest Connecticut Debates Opting Out of Accessory Dwelling Unit Regulations

Cities and towns across southwest Connecticut are weighing whether or not to opt out of a state law regulating accessory dwelling units.

If you’ve tuned into a local government meeting, particularly those involving planning and zoning, in the last few weeks, you’ve probably heard the words “accessory dwelling unit” and “opting out.” But what do those phrases mean?

In 2021, Governor Ned Lamont signed a law, Public Act 21-29, that included a variety of zoning reforms. One of the most notable changes was that it allowed single-family homeowners to create accessory dwelling units on their property, without needing special permission from local officials. However, the bill included an opt-out clause, allowing municipalities to set their own regulations surrounding ADUs. All municipalities have until Jan. 1, 2023 to opt-out. That’s why so many are discussing—and voting on their plans now.

What’s in Public Act 21-29 and what is its purpose?

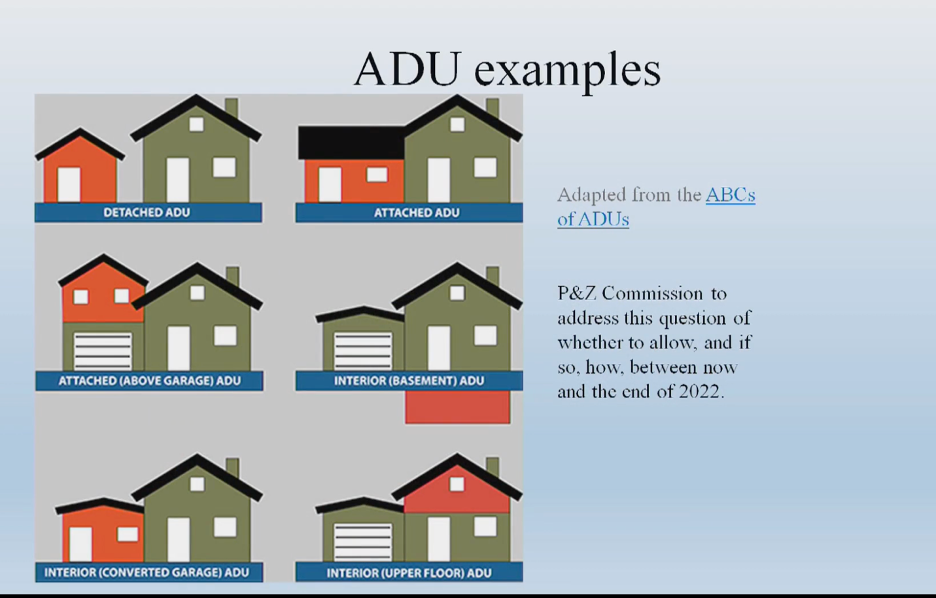

The law allowed accessory dwelling units in single family zones across the state “as of right”—meaning that there’s no special permit or public hearing needed to construct the units. They can be either attached to the main house—such as an attic or garage apartment—or they can be detached, such as a smaller building in the backyard of the main property. The apartments can be up to 1,000 square feet or 30% of the main dwelling on the property.

Many municipalities (including Norwalk, Fairfield, Greenwich, and Westport) already allow for these types of units, according to Francis Pickering, the executive director of WestCog, an agency that provides transportation, environmental, economic, and other planning services to 18 municipalities in western Connecticut. However, the new state law, in addition to allowing ADUs in single family zones, also makes it easier to build one by taking away some of the restrictions.

The idea behind the law, according to advocates and lawmakers who supported it, was that it will help provide more housing, particularly housing that will be affordable and fit into communities. Supporters of the law, such as members of Desegregate CT, a coalition under the Regional Plan Association that advocates for housing policy, said that the bill helps address housing affordability, provides more housing in general, and can allow seniors to “age in place” in their communities.

Pam Ralston, Director of Opening Doors Fairfield County, said in a statement that the law is a “hopeful solution to historical restrictions on the availability of affordable housing stock for the Fairfield County region.”

“Allowing the creation of ADU’s by reducing strict zoning rules will enable homeowners to restructure existing housing quickly with minimal renovation, thereby increasing existing affordable housing available to low-moderate income renters,” Ralston said. “Such strategies also offer older individuals the chance to age in place at family owned properties, young adults with limited income and credit history an opportunity to build rental history, and financially strapped homeowners the enterprise of retaining ownership through access to rental income.”

Christie Stewart, Director of Fairfield County Center for Housing Opportunity, said in a statement that the law was “an important step in ensuring that zoning decisions in our communities better reflect and uphold the values of inclusion and equity that so many Fairfield County and CT residents stand behind.”

However, some of those who opposed the law, argued that it takes away single-family zoning and causes more density in neighborhoods.

State Representative Kim Fiorello, who represents Greenwich and part of Stamford and voted against the bill, told the Land Use and Urban Redevelopment Committee of the Stamford Board of Representatives in June that there has been a push for the state to have more say in zoning issues.

“A whole bunch of new bills were being proposed to say the state has to have a heavier hand in local zoning,” she said.

For instance, if communities don’t opt out of these regulations, accessory dwelling units would be allowed as of right which “doesn’t have a lot of regard for your local regulations,” she said to the committee.

Fiorello said that “there is a drive to disallow” single family zoning across the state.

Local officials have had mixed support for the bill, with some saying it won’t make a huge difference.

Ralph Blessing, the chief of the Land Use Bureau in Stamford, said that he considers accessory dwelling units as “a useful tool” when it comes to addressing the need for affordable housing in the state.

“I don't think it’s the silver bullet to solve the housing crisis that we’re having,” he told the Land Use and Urban Redevelopment Committee of the Stamford Board of Representatives at its June meeting.

Blessing noted that neighboring communities have had accessory dwelling unit regulations in place for a long time, and there haven’t been a large number of accessory dwelling units in the area.

“I wouldn’t put ADUs at the top of my priority list of things to do,” he said.

Dave Keating, a consultant for the Darien Planning and Zoning department, listed off both the pros and cons for the town’s commission in July.

“They increase the housing selection and affordability for renters,” he said. “It increases the resale value of the property.”

However, more people also means more cars, more traffic, and more use of town services, he said.

Still, the law has an opt-out provision meaning that local communities can decide if they want to do their own thing or follow the state rules.

In order to opt out of the state law, the Zoning Board (or Planning and Zoning Board depending on the community) must hold a public hearing to gather feedback and then with a ⅔ majority vote to opt out. That decision is then sent to the municipality’s legislative body, which also must vote with a ⅔ majority to opt out. All of those votes must occur before Jan. 1, 2023.

Why are municipalities opting out or thinking of opting out of Public Act 21-29?

All of the municipalities in our region have already opted out or are currently discussing opting out of the law as of 7/31.

Pickering, the executive director of WestCog, told the Land Use and Urban Redevelopment Committee of the Stamford Board of Representatives at its June meeting that WestCog is advising its members to opt-out and adopt their own regulations.

“We have been advising our members to opt out—largely we support accessory apartments as an innovative way to increase the diversity, availability, and affordability of the housing stock,” he said.

Pickering did emphasize that all communities should have a plan in place.

“If a municipality does opt out, don’t opt out without an action plan,” he said.

While each city and town have cited specific reasons, a few overarching reasons have emerged in the discussions.

Local Control

The biggest and most prevalent reason municipalities have stated for opting out is keeping local control over their zoning.

Pickering said that he’s told his members to “preserve local control,” even if they like the state regulations. The local municipality can basically adopt the same ones as the state locally, but by opting out of the state law they can change and adapt it in the future.

That allows the local municipality to tailor the regulations to local needs, he said, where they can take into account things like sewer and water availability. He noted that there are “many different environments” across the state.

“The regulation may work in some, but not in others,” he said.

Nina Sherwood, a member of the Stamford Board of Representatives, said at that June committee meeting that they, as a city, should have “control over our most valuable asset, our land.”

“For me, as an elected official, I see land use as one of the most important jobs the city has,” she said.

In a letter from Danielle Dobin, Westport’s Planning and Zoning chair, she said that the town would be opting out because “the commission recently adopted an ADU regulation that is appropriate for Westport while allowing for greater flexibility in housing options for existing and new residents.”

Darien’s Planning and Zoning Chair Stephen Olvany voiced support for accessory apartments—particularly those used by family members, such as children returning home after college, but said he wanted the town to have control over the issue.

“I want to be able to maintain local control for the town of Darien,” he said. “We’ve done a great job doing it for all of our stuff. If we opt out, which is what my recommendation is, we can maintain local control and draft our own accessory dwelling unit statute.”

Specific Provisions

Related closely to local control, officials have stated they’d like to either keep or add specific provisions to the ADUs. In Greenwich, for example, homeowners are already allowed to have accessory dwelling units on their property, provided that they are “affordable,”—or for those who make 80% or less of the area median income—or are for those who are seniors and/or disabled. The state law has no such requirements, so Greenwich’s Director of Planning and Zoning Katie DeLuca said they’d like to opt out to keep these regulations in place.

“It’s important we retain our own local regulations, “ she said.

Sherwood said that she would be interested if Stamford passed a similar regulation—requiring ADUs to be affordable.

Norwalk’s Planning and Zoning Commission also voted to opt out so specific regulations could remain in place.

In its opt-out resolution, the commission said it found “that most of the limitations in regulating accessory dwelling units included in Public Act No. 21-29 are acceptable provided that some additional restrictions.”

Those additional restrictions include a smaller maximum size and height of the unit than the state allowed, more a setback from the front yard, and the detached units follow architectural designs for the areas in the city. The city also plans to require “periodic renewals” for accessory dwelling units, which is not in the state law.

In Fairfield, where accessory dwelling units have been allowed in many districts since 1986, the town voted to opt out to keep its regulations in place.

“The Accessory Apartment Regulations were most recently amended in February of 2021 and very similar to the required state language, “ a letter from the town’s Planning Director Jim Wendt reads.

The town has two main reasons for opting out. The first is that it would like to keep restricting accessory dwelling units from being built in the Beach District due to “the unique and discreet geography,” of that area, Wendt said in his letter.

The second is that the state law allows for accessory units in detached structures in any district, regardless of lot size, while the town believes that “detached units should not be permitted in all districts,” particularly those with smaller lots.

In Darien, Dave Keating, who is working as a consultant for the Planning and Zoning department, said that he supported the town opting out because there were a lot of issues that needed to be addressed, such as parking requirements.

Questions Around Enforcement

Currently in Stamford, accessory dwelling units are not allowed, but many representatives said that there are “illegal apartments” that already exist, such as people renting out their basements, and they questioned how to differentiate between legal ones and illegal ones for enforcement issues.

“When you do drive around, you do see a lot of illegal apartments all over Stamford,” Representative Jeff Stella said. “If we’re peppering all of Stamford with legal ADUs, illegal ADUs—we don't have enough enforcement for this.”

Stella said that he thinks they need to “clean up” what’s taking place in the city first, before adding more units.

Communities must have both the zoning and legislative votes completed by Jan. 1, 2023 or else the state regulations will go into effect.